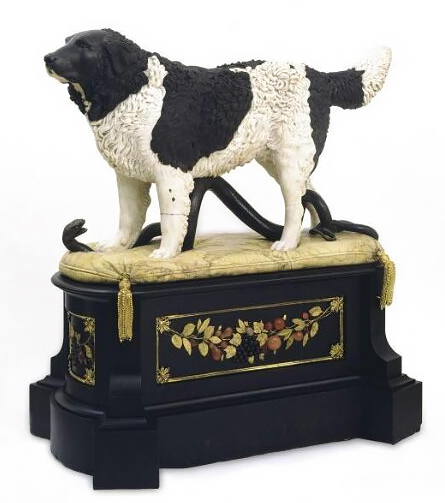

Bashaw, The Faithful Friend of Man

Bashaw, The Faithful Friend of Man

Trampling Under Foot His Most Insidious Enemy (1831-1834)

by

Matthew Cotes Wyatt

This statue is of the same dog, Bashaw, featured in the Sir Edwin Landseer painting Off to the Rescue (1827). It is worth noting that this is the earliest statue of a Newfoundland that I am aware of.

("Bashaw," by the way, is an earlier form of the Turkish word "Pasha," which was, back in the day, a title of high military or political rank.)

This statue is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; their description of this piece is as follows: "This life-size sculpture of a Newfoundland dog was commissioned by John William Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley, to commemorate his favourite dog. It was to be placed in Lord Dudley's house in Park Lane, London. The dog was sent from Lord Dudley's country seat, Himley Hall, Staffordshire, to London to sit to Wyatt 50 times. Lord Dudley died in 1833, before the sculpture was finished, and a dispute about the price (£5,000) between Wyatt and Lord Dudley's executors was never resolved, the sculpture remaining in Wyatt's possession until his death in 1862."

More about Bashaw, whose importance in Newfiedom goes beyond being the subject of what I believe is the very first statue of a Newfoundland as well as the first Newf (to my knowledge) who was the subject of BOTH a painting and a sculpture:

On May 29, 1829, there appeared in The Times (London) newspaper a "lost dog" notice regarding a Newfoundland who responded to the name "Bashaw." This is surely the same dog, for as you can see in the description of the Wyatt statue quoted above, the dog's owner, the 1st Earl Dudley, lived in Park Lane, London, which is precisely where the dog in the newspaper notice was reported missing. At least we know this particular Bashaw was found and returned to its owner, since the statue of Bashaw wasn't begun until several years after the "lost Newf" notice appeared. It may also be worth noting that the reward offered for the return of the missing Bashaw was two guineas — approximately $240 US in 2020 — which was more than double the usual reward offered for lost Newfoundlands at this time, strongly indicating the lost Newf belonged to a well-to-do owner.)

Bashaw's name appears in The Times (London) again in 1834, in an announcement that the statue is available for public viewing. This was probably an attempt by Wyatt to recoup some of the cost of the statue's creation, as Bashaw's owner had died the year before without paying for the statue, and the executors of the Earl's estate likewise refused to compensate Wyatt, which is why the statue remained with Wyatt for the rest of his life and finally ended up in the V&A museum.

I suspect it was that public exhibition which led to the statue of Bashaw getting some attention in the March, 1834, issue of Sporting Magazine:

A perfectly novel and most interesting specimen of art has recently emanated from the chisel of that eminent sculptor, Mr. M. C. Wyatt. It is a statue of the late Lord Dudley's favorite and well-known Newfoundland dog Bashaw, which is executed with such complete ingenuity as to give an exact resemblance of the animal in the most minute particular, amounting almost to an appearance of actual animation, the artist having been singularly fortunate in procuring marble of the various hues to produce this effect. The tout ensemble is really surprising. (427)

Although if it is the case that the above notice was prompted by Wyatt's public showing of the statue, Sporting Magazine didn't do Wyatt any favors by neglecting to mention that fact.

A more substantive and equally positive (anonymous) review of Wyatt's statue of Bashaw appeared in the September, 1834, issue of American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine, under the title "Honor of Merit":

[Who has not owned and loved, and had the misfortune to lose, a favorite dog — a LUBIN or a LEADER —

"— in life the warmest friend,

The first to welcome, foremost to defend," —

that he would gladly have preserved the form of, as is here stated?]

We have attended a private view of what may be considered a great curiosity in art. The late Lord Dudley was possessed of the beau ideal of a dog. It was a Newfoundland, and of more than ordinary size, and of most amazing beauty. His Lordship loved the animal — and determined that his memory should, if possible, be perpetuated. As to the manner in which this was to be achieved, he entertained a peculiar notion, which was, that in all respects a model should be made of him, which should not, like the generality of sculpture, merely give the full form as in a statue, or the outline as in bas-relief, but that an accurate representation of the figure should be given, even to the color of the coat and the expression of the eye. This was to be done in marble, and to Mr. M. C. Wyatt, the difficult commission was given. To say that he has succeeded is the highest and best praise that can be bestowed on a work replete with so many obstacles. The statue of the beautiful beast is placed on a jasper pedestal, the base of which is surrounded by fruit and flowers in alto relievo, curiously formed by precious stones. On the pedestal is a cushion of Sienna colored marble, looking as soft as if the lightest foot would make a print mark. On this cushion stands the dog. A bronze figure of a serpent is beneath him, which the powerful animal had crushed with his paw, the introduction of which at once adds to the interest of this curious piece of statuary, and ingeniously serves as a support to the ponderous weight of the dog. Some method must have been adopted for the sustaining so cumbrous a load beyond the mere support afforded by the legs, and nothing of a more effectual nature could in our opinion have been introduced. But the ingenuity, and, in our estimation, the great merit of the work, consists in the singularly felicitous manner in which the artists has represented the shaggy coat in the different colored marble, making the black so beautifully overlay and intermix with the white. The head is also truly beautiful, for not only the introduction of gems of an exact color fill up the sockets of the eyes, but the fleshy tint which is observable at the extremity of the white part of the eye is managed with the same extraordinary kind of fidelity. The nose, by the insertion of porous looking black marble, is made to bear the appearance of dewy moisture, so commonly observable; and it requires no exercise of the fancy to suppose, that if touched a sensation of moisture would be experienced from the contact. [English paper. (34 - 35)

Bashaw's name will be invoked in The Times on several occasions in 1836, when the hucksterish London dog seller J. S. Pardy will post several advertisements offering "Some splendid Newfoundlands and Whelps, got by the Great Bashaw." Pardy will even, in October of 1836, offer for sale "the Young Bashaw," though whether that dog truly was a son of the original Bashaw (who would have been at least 10 years old by this time) or was simply a huckster's claim may never be known.

An obituary of Matthew Cotes Wyatt in the popular and influential Gentleman's Magazine in March of 1862 paid particular attention to this statue of Bashaw.

This statue is also mentioned by the noted Victorian art and social critic John Ruskin in his book Fors Clavigera, and it is not pretty.

More recently, there's a brief and highly entertaining article discussing this statue on the NCA website, reprinted from a 1978 NewfTide.

Even more recently, Bashaw was mentioned in not one but two book reviews in the New York Times. Both were discussing 19th-Century Sculpture by the noted art historian H. W. Janson. The first review was titled "19th-Century Sculpture as Seen by a Noble Spirit," by John Russell, and appeared in the March 24, 1985, issue. Russel remarks that some senior art scholars would have preferred " 'to pass over in silence the sculpture for which Wyatt was most famous in his lifetime — the "commissioned lifesize portrait of Lord Dudley's favorite Newfoundland dog in black, gray and white marble, with gemstones for eyes, on a yellow marble cushion, trampling a large bronze snake.' It was, after all, no less a critic than John Ruskin who said that it was 'the most perfectly and roundly ill-done thing which I ever saw produced in art.' But Jansen wasn't going to sell the dog short, though he did say that 'the snake was an afterthought, its main function being to support the weight of the dog's belly.' "

The second review, published on June 30, 1985, and written by Celia Betsky McGee, notes that "Much 19th-Century sculpture was created for private purposes . . . not the least popular of which proved to be "Bashaw," Matthew Coates Wyatt's often-exhibited portrait of a Newfoundland dog."

Bashaw was also alluded to in a May 14, 1989, article in the New York Times about a controversial re-organization of the Victoria & Albert's administration, which it was feared might negatively impact the broad appeal of the museum's diverse collection, which covers a variety of historical periods and styles and art forms, including "the Newfoundland dog that was sculpted in England in 1834 and is made of colored marbles, with eyes of topaz and sardonyx?"

Bashaw even has his own Wikipedia entry.

image courtesy of the V&A Museum

image courtesy of the V&A Museum

Click the image just above to read more about, and see more photos of, Wyatt's statue of Bashaw

at the Victoria and Albert Museum.