[ Kingston / Stories of the Sagacity of Animals ]

Kingston (1814 - 1880) was a popular and prolific English author, principally of boy's adventure stories.

This work for young adult readers is essentially a collection of previously-published anecdotes, many of which are here presented with brief morals, almost as fables, for the edification of children.

Text is from the first edition, published 1879 (Thomas Nelson and Sons, London). The illustrations in this volume are by Harrison Weir (1824 - 1906), the noted and prolific English animal illustrator and author who, according to his Wiki entry, is also known as "the Father of the Cat Fancy" for organizing the very first cat show in England in 1871. Several illustrations of Newfs by Weir can be found in the "Fine Arts" section of The Cultured Newf.

The first anecdote is adapted from an article in the Times (London), that was published in that paper in 1858; read it here at The Cultured Newf.

A young Newfoundland dog, living in Glasgow a few years ago, acted, under similar circumstances, very much as Alp did. As he sometimes misbehaved himself, a whip was kept near him, which was occasionally applied to his back. He naturally took a dislike to this article, and more than once was found with it in his mouth, moving slyly towards the door.

Being shut up at night in the house to watch it, he in his rounds discovered the detested instrument of punishment. To get rid of it, he attempted to thrust it under the door. It stuck fast, however, by the thick end. A few nights afterwards he again got hold of the whip, and persevered till he shoved through the thick end, when some one passing by carried it off. On being questioned as to what had become of the whip, he betrayed his guilt by his looks, and slunk away with his tail between his legs.

The second Newf anecdote, "Byron, the Newfoundland Dog," is more overtly moralizing:

Next on my list of canine favourites stands a noble Newfoundland dog named Byron, which belonged to the father of my friend, Mrs F—. On one occasion he accompanied the family to Dawlish, on the coast of Devonshire. His kennel was at the back of the house. Whenever his master was going out, the servant loosened Byron, who immediately ran round, never entering the house, and joined him, accompanying him in his walk.

One day, after getting some way from home, his master found that he had forgotten his walking-stick. He showed the dog his empty hands, and pointed towards the house. Byron, instantly comprehending what was wanted, set off, and made his way into the house by the front door, through which he had never before passed. In the hall was a hatstand with several walking-sticks in it. Byron, in his eagerness, seized the first he could reach, and carried it joyfully to his master. It was not the right one, however. Mr — on this patted him on the head, gave him back the stick, and again pointed towards the house. The dog, apparently considering for a few moments what mistake he could have made, ran home again, and exchanged the stick for the one his master usually carried. After this, he had the walking-stick given him to carry, an office of which he seemed very proud.

One day while thus employed, following his master with stately gravity, he was annoyed during the whole time by a little yelping cur jumping up at his ears. Byron shook his head, and growled a little from time to time, but took no further notice, and never offered to lay down the stick to punish the offender.

On reaching the beach, Mr — threw the stick into the waves for the dog to bring it out. Then, to the amusement of a crowd of bystanders, Byron, seizing his troublesome and pertinacious tormentor by the back of the neck, plunged with him into the foaming water, where he ducked him well several times, and then allowed him to find his way out as best he could; while he himself, mindful of his duty, swam onward in search of the now somewhat distant walking-stick, which he brought to his master’s feet with his usual calm demeanour. The little cur never again troubled him.

Be not less magnanimous than Byron, when troublesome boys try to annoy you whilst you are performing your duties; but employ gentle words instead of duckings to silence them. Drown the yelping curs — bad thoughts, unamiable tempers, temptations, and such like — which assault you from within.

The next Newf anecdote is "The Newfoundland and the Marked Shilling," a story whose earliest publication I am aware of is in James Fennell's Natural History of British and Foreign Quadrupeds, first published in 1841. This anecdote was frequently repeated by other writers on animal sagacity.

I must now tell you a story which many believe, but which others consider “too good to be true.”

A gentleman who owned a fine Newfoundland dog, of which he was very proud, was one warm summer’s evening riding out with a friend, when he asserted that his dog would find and bring to him any article he might leave behind him. Accordingly it was agreed that a shilling should be marked and placed under a stone, and that after they had proceeded three or four miles on their road, the dog should be sent back for it. This was done—the dog, which was with them, observing them place the coin under the stone, a somewhat heavy one. They then rode forward the distance proposed, when the dog was despatched by his master for the shilling. He seemed fully to understand what was required of him; and the two gentlemen reached home, expecting the dog to follow immediately. They waited, however, in vain. The dog did not make his appearance, and they began to fear that some accident had happened to the animal.

The faithful dog was, however, obedient to his master’s orders. On reaching the stone he found it too heavy to lift, and while scraping and working away, barking every now and then in his eagerness, two horsemen came by. Observing the dog thus employed, one of them dismounted and turned over the stone, fancying that some creature had taken refuge beneath it. As he did so, his eye fell on the coin, which—not suspecting that it was the object sought for—he put into his breeches pocket before the animal could get hold of it. Still wondering what the dog wanted, he remounted his steed, and with his companion rode rapidly on to an inn nearly twenty miles off, where they purposed passing the night.

The dog, which had caught sight of the shilling as it was transferred to the stranger’s pocket, followed them closely, and watched the sleeping-room into which they were shown. He must have observed them take off their clothes, and seen the man who had taken possession of the shilling hang his breeches over the back of a chair. Waiting till the travellers were wrapped in slumber, he seized the garment in his mouth—being unable to abstract the shilling—and bounded out of the window, nor stopped till he reached his home. His master was awakened early in the morning by hearing the dog barking and scratching at his door. He was greatly surprised to find what he had brought, and more so to discover not only the marked shilling, but a watch and purse besides. As he had no wish that his dog should act the thief, or that he himself should become the receiver of stolen goods, he advertised the articles which had been carried off; and after some time the owner appeared, when all that had occurred was explained.

The only way to account for the dog not at first seizing the shilling is, that grateful for the assistance afforded him in removing the stone, he supposed that the stranger was about to give him the coin, and that he only discovered his mistake when it was too late. His natural gentleness and generosity may have prevented him from attacking the man and trying to obtain it by force.

Patiently and perseveringly follow up the line of duty which has been set you. When I see a boy studying hard at his lessons, or doing his duty in any other way, I can say, “Ah, he is searching for the marked shilling; and I am sure he will find it.”

The next anecdote to mention a Newf is similar to several earlier stories about Newfoundlands learning to use a servant's bell or hand bell:

. . . my friend Mrs F— mentioned the case of a Newfoundland dog, which was one day accidentally shut up in the dining-room, when the family were out. He scratched at the door and whined loudly for a length of time; but though the servants heard him, they paid no attention. At length, as if the thought had suddenly occurred to him that whenever the bell was rung the door was opened, he actually rang the bell right heartily. A servant instantly obeyed the summons, when out sprang the dog, wagging his tail with delight at the result of his sagacious experiment, and leaving the man in amazement at finding no person in the room.

The next story closely follows an anecdote in T. Gwynne's The School for Fathers, a moralizing book for young readers first published in 1852 and whose author's real name was Josepha Heath Galston.

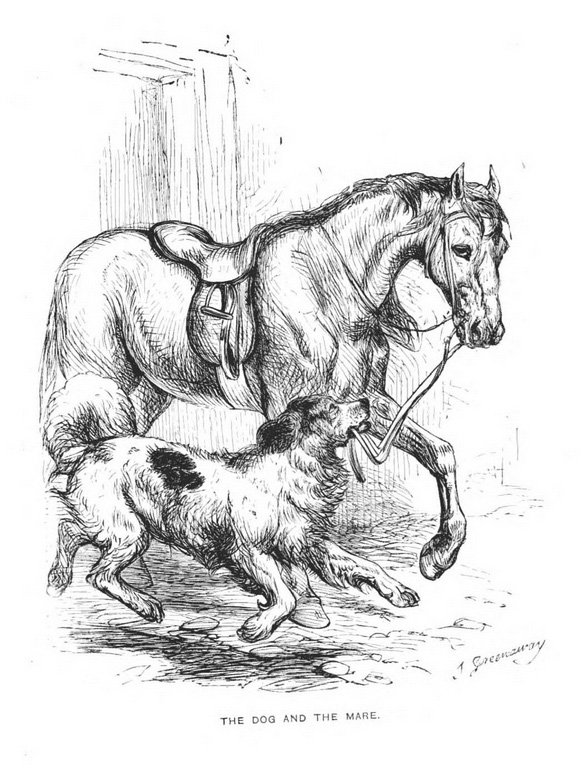

Dogs and horses frequently form friendships. A Newfoundland dog had attached himself to a mare belonging to his master, and seemed to consider himself especially the guardian of his less sagacious companion. Whenever the groom began to saddle the mare, the dog used to lie down with his nose between his paws, watching the proceeding. The moment the operation was finished, up jumped the dog, seized the reins in his mouth, and led the mare to her master, following him in his ride.

On returning home, the reins being again given to him, he would lead his friend back to the stable. If, on his arrival, the groom happened to be out of the way, he would bark vehemently till he made his appearance, and then hand over his charge to him.

You may be young and little, but if you exercise discretion and judgment, you may assist those much bigger and older than yourself. Learn from the dog, however, not to give yourself airs in consequence; you will have simply performed your duty in making yourself useful.

Up next is "The Newfoundland Dog and the Thievish Porter," taken from Edward Jesse's Anecdotes of Dogs, first published in 1846.

A grocer owned a Newfoundland dog, which used frequently to take charge of the shop. While thus lying down with his nose between his paws, he observed one of the porters frequently visiting the till. He suspected that the man had no business to go there. He therefore watched him, and, following him, observed him hide the money he had taken in the stable. The dog, on this, attempted to lead several persons in whom he had confidence towards the place, by pulling in a peculiar manner at their clothes. They took no heed of him, till at length one of the apprentices going to the stable, the dog followed him and began scratching at a heap of rubbish in a corner. The young man’s attention being aroused, he watched the animal, which soon scratched up several pieces of money. The apprentice, collecting them, evidently to the dog’s satisfaction, took them to his master, who marked them, and restored them to the place where they were discovered.

The porter, who for some other cause was suspected, was at length arrested, when some of the marked coin was found on him. On being taken before a magistrate, he confessed his guilt, and was convicted of the theft.

The next Newf-related story, "The Newfoundland Dog Saving the Mastiff," is taken from the same source.

I must tell you one more anecdote of two dogs of a similar character to one I gave you a few pages back, but in this instance they were professed enemies. It happened at Donaghadee, where a pier was in course of building.

Two dogs — one a Newfoundland, and the other a mastiff — were seen by several people engaged in a fierce and prolonged battle on the pier. They were both powerful dogs, and though good-natured when alone, were much in the habit of thus fighting whenever they met. At length they both fell into the sea, and as the pier was long and steep, they had no means of escape but by swimming a considerable distance. The cold bath brought the combat to an end, and each began to make for the land as best he could.

The Newfoundland dog speedily gained the shore, on which he stood shaking himself, at the same time watching the motions of his late antagonist, who, being no swimmer, began to struggle, and was just about to sink. On seeing this, in he dashed, took the other gently by the collar, kept his head above water, and brought him safely to land.

After this they became inseparable friends, and never fought again; and when the Newfoundland dog met his death by a stone waggon running over him, the mastiff languished, and evidently mourned for him for a long time.

Let this incident afford us great encouragement to love our enemies, and to return good for evil, since we find the feeling implanted in the breast of a dog to save the life of his antagonist, and to cherish him afterwards as a friend.

We may never be called on to save the life of a foe; but that would not be more difficult to our natural disposition than acting kindly and forgivingly towards those who daily annoy us — who injure us or offer us petty insults.

The next story, "The Newfoundland Punishing the Little Dog," has its origin in an anecdote first told in the Rev. Thomas Hancock's 1824 Essay on Instinct.

You remember the way Byron punished his troublesome little assailant. Another Newfoundland dog, of a noble and generous disposition, was often assailed in the same way by noisy curs in the streets. He generally passed them with apparent unconcern, till one little brute ventured to bite him in the back of the leg. This was a degree of wanton insult which could not be patiently endured; so turning round, he ran after the offender, and seized him by the poll. In this manner he carried him to the quay, and holding him for some time over the water, at length dropped him into it. He did not, however, intend that the culprit should be drowned. Waiting till he was not only well ducked, but nearly sinking, he plunged in and brought him safely to land.

Could you venture to look a Newfoundland dog in the face, and call him a brute beast, if you feel that you have acted with less generosity than he exhibited!

The next Newf anecdote, "Neptune, or Faithful to Trust," is from Thomas Bell's A History of British Quadrupeds, 1837.

At an inn in Wimborne in Dorsetshire, near which town I resided, was kept, some years ago, a magnificent Newfoundland dog called Neptune. His fame was celebrated far and wide. Every morning he was accustomed, as the clock of the minster struck eight, to take in his mouth a basket containing a certain number of pence, and to carry it across the street to the shop of a baker, who took out the money, and replaced it by its value in rolls. With these Neptune hastened back to the kitchen, and speedily deposited his trust.

It is remarkable that he never attempted to take the basket, nor even to approach it, on Sunday mornings, when no rolls were to be obtained.

On one occasion, when returning with the rolls, another dog made an attack upon the basket, for the purpose of stealing its contents. On this the trusty fellow, placing it on the ground, severely punished his assailant, and then bore off his charge in triumph.

He met his death—with many other dogs in the place—from poison, which was scattered about the town by a semi-insane person, in revenge for some fancied insult he had received from the inhabitants.

Like trusty Neptune, deserve the confidence placed in you, by battling bravely against all temptations to act dishonestly. Your friends may never know of your efforts to do so, but your own peace of mind will be reward enough.

The next anecdote, The Newfoundland Dog and the Hats," is also from Edward Jesse's Anecdotes of Dogs, 1846.

In sagacity, the Newfoundland surpasses dogs of all other breeds.

Two gentlemen, brothers, were out shooting wild-fowl, attended by one of these noble animals. Having thrown down their hats on the grass, they together crept through some reeds to the river-bank, along which they proceeded some way, after firing at the birds. Wishing at length for their hats—one of which was smaller than the other—they sent the dog back for them. The animal, believing it was his duty to bring both together, made several attempts to carry them in his mouth. Finding some difficulty in doing this, he placed the smaller hat within the larger one, and pressed it down with his foot. He was thus, with ease, enabled to carry them both at the same time.

Perhaps he had seen old-clothes-men thus carrying hats; but I am inclined to think that he was guided by seeing that this was the best way to effect his object.

There are two ways of doing everything—a wrong and a right one. Like the Newfoundland dog, try to find out the right way, and do what you have to do, in that way.

Next, "The Newfoundland Dog and the Wreck," is from William Youatt's The Obligation and Extent of Humanity to Brutes (1839).

How often has the noble Newfoundland dog been the means of saving the lives of those perishing in the water!

A heavy gale was blowing, when a vessel was seen driving toward the coast of Kent. She struck, and the surf rolled furiously round her. Eight human beings were observed clinging to the wreck, but no ordinary boat could be launched to their aid; and in those days, I believe, no lifeboats existed,—at all events, not as they do now, on all parts of the coast. It was feared every moment that the unfortunate seamen would perish, when a gentleman came down to the beach, accompanied by a Newfoundland dog. He saw that, if a line could be stretched between the wreck and the shore, the people might be saved; but it could only be carried from the vessel to the shore. He knew how it must be done.

Putting a short stick in the mouth of the animal, he pointed to the vessel. The courageous dog understood his meaning, and springing into the sea, fought his way through the waves. In vain, however, he strove to get up the vessel’s side; but he was seen by the crew, who, making fast a rope to another piece of wood, hove it toward him. The sagacious animal understood the object, and seizing the piece of wood, dragged it through the surf, and delivered it to his master. A line of communication was thus formed between the vessel and the shore, and every man on board was rescued from a watery grave.

The final Newf-related anedote, "Dandie, the Miser," is taken from Thomas Brown's Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs, first published in 1829.

Dandie, a Newfoundland dog belonging to Mr McIntyre of Edinburgh, stands unrivalled for his cleverness and the peculiarity of his habits. Dandie would bring any article he was sent for by his master, selecting it from a heap of others of the same description.

One evening, when a party was assembled, one of them dropped a shilling. After a diligent search, it could nowhere be found. Mr McIntyre then called to Dandie, who had been crouching in a corner of the room, and said to him, “Find the shilling, Dandie, and you shall have a biscuit.” On this Dandie rose, and placed the coin, which he had picked up unperceived by those present, upon the table.

Dandie, who had many friends, was accustomed to receive a penny from them every day, which he took to a baker’s and exchanged for a loaf of bread for himself. It happened that one of them was accosted by Dandie for his usual present, when he had no money in his pocket. “I have not a penny with me to-day, but I have one at home,” said the gentleman, scarcely believing that Dandie understood him. On returning to his house, however, he met Dandie at the door, demanding admittance, evidently come for his penny. The gentleman, happening to have a bad penny, gave it him; but the baker refused to give him a loaf for it. Dandie, receiving it back, returned to the door of the donor, and when a servant had opened it, laid the false coin at her feet, and walked away with an indignant air.

Dandie, however, frequently received more money than he required for his necessities, and took to hoarding it up. This was discovered by his master, in consequence of his appearing one Sunday morning with a loaf in his mouth, when it was not likely he would have received a present. Suspecting this, Mr McIntyre told a servant to search his room—in which Dandie slept—for money. The dog watched her, apparently unconcerned, till she approached his bed, when, seizing her gown, he drew her from it. On her persisting, he growled, and struggled so violently that his master was obliged to hold him, when the woman discovered sevenpence-halfpenny. From that time forward he exhibited a strong dislike to the woman, and used to hide his money under a heap of dust at the back of the premises.

People thought Dandie a very clever dog—as he was—but there are many things far better than cleverness. It strikes me that he was a very selfish fellow, and therefore, like selfish boys and girls, unamiable. He was an arrant beggar too. I’ll say no more about him. Pray do not imitate Dandie.

Kingston also makes a metaphorical reference in one of his adventure novels, Peter the Whaler, treated here at The Cultured Newf.