[ Brough / "A Newfoundland and Bull-Dog Story" ]

Robert Brough (1828 - 1860) was an English writer of popular novels, plays, and verse, much of it comic or satiric.

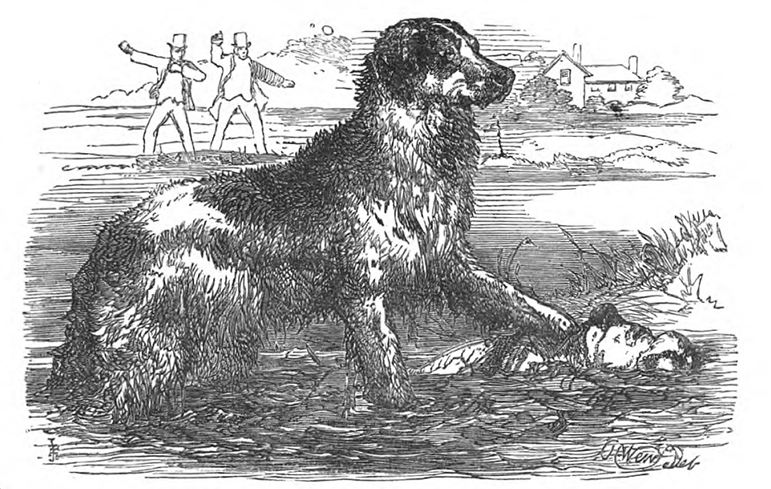

This short story (which seems to have a factual basis) about a Newfoundland's getting revenge on his bulldog tormentor was first published in Brough's collection, published in the year of his death, Miss Brown: A Romance; and other tales in prose and verse (London: James Blackwood). The volume was illustrated by W. M'Connell, Kenny Meadows, H. G. Hine, and T. MacQuoid; the illustration of a Newfoundland drowning a bulldog which accompanied this story may be found right here:

A NEWFOUNDLAND AND BULL-DOG STORY.

THE Newfoundland dog's name was Tippoo. The bull-dog's was Boxer. They were neighbours of mine in early life, and I was personally acquainted with both animals; though on widely different grounds of intimacy. Tippoo was my bosom friend, and I loved him. Boxer was Tippoo's most relentless and cruel enemy, for which reason I hated him, and would have sought his blood, but that — being of tender years, and cautious temperament, conscious, moreover, of presenting an appetising display of bare leg, insisted on by the sumptuary laws of the period — I thought it possible that he might take a fancy to mine; and so, as a rule, kept discreetly out of his way. For he was an ugly dog was Boxer, and a vicious; a bandy-legged, black-muzzled, truculent, nervous-eared, tight-skinned, implacable, ill-conditioned dog, very like my beau ideal of what the Champion of England ought to be. I am privileged to annex his portrait, so that you will be enabled to judge for yourselves. Observe the ferocity of his bead-like eyes, and the aggressive protrusion of gladiatorial chest. In Justice to the dead (for I am happy to anticipate the announcement of the offensive brute's demise), I feel bound to call your attention to a somewhat humourous expression of countenance, which has been faithfully preserved by the artist, and which I can honestly assert to be the only redeeming characteristic I remember to have noticed in the creature's generally repulsive appearance.

Tippoo was a very different kind of quadruped. I believe him to have been the most perfect gentleman that ever stood upon four legs, just as I believe Boxer to have been the most consummate ruffian that ever was lifted, by the agency of hemp-cord, from any number of those locomotive supports. Tippoo was nearly as tall as myself. I could just look over his glossy silken-ringletted back, when cuddling his noble neck. He wore a full suit of black and white, particularly snowy at the bosom. He was as strong as a lion, and as gentle as a lamb. Next to playing with

me, (which I am proud to believe was his favourite pastime), he delighted in nothing so much as the exercise of carrying in his mouth a favourite cat, attached to the household of which he was so conspicuous a member, to

the bottom of a steep lawn; then releasing, and running a race with her to the top. The cat was generally the winner,

and always seemed to enjoy the triumph immensely. To this day, I believe Tippoo made a point of running slowly

on purpose, so as gallantly to concede victory to the weaker vessel.

Tippoo belonged to a country gentleman (a sort of "half-squire," as they would say in Ireland) who resided opposite to my father's house. In my opinion, and in that of a majority of my playmates, Tippoo was the most important and respectable inhabitant of the village, up to the advent of Boxer, who came among us unexpectedly, on a visit to Tippoo's master, in the train of a sporting lawyer of detestable memory. As soon as that subversive brute (Boxer—not the sporting lawyer) had made his appearance, we felt much as the loyal servants of King Louis the Sixteenth must have felt on the outbreak of the Great French Revolution. Monarchy was deposed in favour of blackguardism. But the blackguard was strong and merciless, with a set of terrible white teeth ever eager to bite. So that we poor little partisans of the ancient regime were fain to clench our impotent fists in secret.

Tippoo had no chance against Boxer. What is the use of a well-dressed gentleman, let him be never so strong or skilful in the use of his clenched digits, descending from his cabriolet to do battle with a scavenger armed with a mud shovel? He sedulously avoided Boxer, who, on his side, lost no opportunity of hunting out and persecuting Tippoo. Tippoo was losing character dreadfully. He neglected his food, kept his kennel, and was unanimously pronounced a coward of the most contemptible stamp. His very court flatterers (we were no better than the more matured and ambitious of our species), began to blush for their sovereign's pusillanimity.

One day the masters of the two dogs stood on the lawn already alluded to, in amicable converse with a third person, no other than my own father, to whom I am indebted for the details of this instructive story. Boxer stood between his proprietor's legs, which, like his own, were bandy. I have the keenest recollection of those legs —

master's and dog's — and I remember that the whole six were modelled upon the same pattern, which was one

extremely distasteful to my feelings.

"Holloa!" said my father, "here comes Tip! We shall soon see him sneak away when he discovers Boxer. Dreadful coward, that big dog of yours, Matthews, to be sure."

"Well, he used not to be so," said Tippoo's master reluctantly, "but I must confess that since Wilkins has been here with his bull, the overgrown cur has made me ashamed of him."

"No call for that," said the bull-dog's master, "better dogs than Tip have funked at the sight of my Boxer. By

Jove, though, he hasn't bolted yet. He'd better, or Boxer will murder him!"

Boxer certainly showed playful indications of a desire to attempt that experiment, by pricking up his ears and

starting off at a brisk trot in the direction of Tippoo, who, however, to the astonishment of the spectators, made no

movement towards recovering the shelter of his easily accessible kennel. On the contrary, he seemed to wait for and encourage his aggressor's attack.

"The dog's mad, clearly," said the lawyer. "Looks like it." Mr. Matthews assented. "He isn't acting like a dog in his senses."

"Getting very near the water though, for a mad dog," observed my father.

And, in truth, to get near the water, was the main object of Tippoo, than whom a more thoroughly sane dog did not exist at that epoch of canine history.

There was a deep dyke running at the bottom of the lawn, fed from the reservoir of a neighbouring tin-mill, and which had been greatly swollen by recent rains.

Tippoo, keeping his large full eyes carefully fixed upon his approaching foe, sidled in a coquettish, serpentine manner towards the brink of this artificial stream. There the bull-dog flew at and pinned him. Tippoo crouched on the grass prostrate, submitting to the outrage without a growl.

"Call him off, Wilkins," said Tippoo's master, in excited tones. "The purest Newfoundland in the county! I wouldn't have him injured for twenty pounds!"

"Hi! Boxer! Here boy! Good dog! Let go!" the sporting lawyer clamoured, as a shower of sticks and stones

were launched by the trio of spectators to enforce the command.

But Boxer would not let go, and Tip would not resist or run. He merely kept on slipping, sideling, and lumbering towards the brink of the water, dragging the bull-dog with him by the mere inert force of his superior weight

Suddenly a splash was heard, and the triumph of Boxer was at an end. The combatants had rolled together into the swift, deep current of the dyke, and there they speedily changed places. I say "speedily," narrating as I do an actual fact; though I am aware that it may seem to require some explanation, inasmuch as the grip of a bull-dog is supposed to be a final affair, lasting the life-time of the pinner or the pinned. I can only suggest that my gentlemanly friend Tippoo was from the first so completely on the alert, as to prevent his ruffianly antagonist from getting a sure and firm hold. However that may be, Tippoo, released from custody, in his turn seized his assailant by the neck; held him under the water and drowned him! The brave, sagacious water-dog, wrongly imagined to be a coward, knew his own power in his own element, and had watched his opportunity. Would that we were all aswise!

Ere the just execution had been thoroughly accomplished, Tippoo's glossy, patrician hide was pretty well cut to pieces by the missiles now hurled at him instead of his aggressor. But he received them all without a wince, till he felt that his enemy under the water was thoroughly dead. Then he brought the ignoble carcass out of the stream, between his teeth; threw it on the grass with a jerk, and with his fore-paw resting on its flank with a calmly defiant expression, that might clearly be translated by the words,

"No, let this dirty, ugly rascal presume to take liberties with his betters. Make the best of him as he lies

there!"

I know this story to be a true one, for my father told it to me. Moreover, I remember exulting over the sight of the drowned Boxer's disfigured remains (just the least thing in the world ashamed of the feeling, perhaps, but certainly felt it), and doing my best to console my darling Tippoo for his unsightly wounds, by gifts of stolen refreshment — the best medicine I knew how to offer. I suppose that Tippoo, also, is dead by this time. Most of my early friends are, and it may be my turn next, as likely as not. I have finished for the present. (256 - 261)

There is one other Newfoundland-related story of which I am aware which features a dog with the unusual name of "Tippoo": an article on waterfowl hunting that appeared in the November 1861 issue of Sporting Magazine, which is treated here at The Cultured Newf.